By Bryan Delano

The film X-ray era is fully behind us, and we are now entering the second and third generations of digital 2D panoramic/cephalometric technology. The first models of digital X-rays, available in the late 1990s, were film-to-digital upgrades. In the early 2000s, direct digital 2D options were introduced. Today, practices have the option of implementing either new or pre-owned digital X-ray technology at a fraction of the cost of just ten years ago.

The film X-ray era is fully behind us, and we are now entering the second and third generations of digital 2D panoramic/cephalometric technology. The first models of digital X-rays, available in the late 1990s, were film-to-digital upgrades. In the early 2000s, direct digital 2D options were introduced. Today, practices have the option of implementing either new or pre-owned digital X-ray technology at a fraction of the cost of just ten years ago.

As some digital panoramic models reach almost twenty years of age, and most first-generation cone beam units are over ten years of age, warranties have expired, repairs are more frequent, and the cost and availability of parts is challenging. Additionally, software drivers that control these units are not keeping up with modern computer operating systems, limiting available compatible options in the event of a PC failure. When faced with these obstacles, a practitioner has the option to either invest in a costly repair or purchase a replacement unit.

Just like any modern technology, repairing an X-ray unit can range from a ten-dollar simple fuse replacement, to tens of thousands of dollars when replacing a failed sensor. Please see the guidelines below when faced with X-ray component failures.

Digital sensor failure

Unfortunately, there are few, if any viable sensor repair resources, so the replacement of the actual sensor is often the only option with a digital sensor failure. Some X-ray models such as Sirona, Planmeca and Instrumentarium are formatted with cartridge-type sensors that can be moved between pan and ceph. A pan sensor can only be used to capture a panoramic image, but a cephalometric sensor can be used to take a pan OR a ceph. Switching the sensor between the pan and ceph is easy and can provide a long-term solution or can buy time to research other options. It’s never good to feel pressured to make an expensive purchase quickly, so this option can help extend the decision-making period. Purchasing a new sensor can range from $3,000 to $15,000, depending on the manufacturer, but there are other options to consider. For example, often you can find X-ray sensors on eBay that offer Buyers Protection. This allows a buyer to receive the sensor, test it thoroughly, and return it for a full refund if it is defective.

“We don’t know what is wrong”

Many dealer technicians rely on the X-ray manufacturer for support. When your tech arrives, they inevitably will immediately contact the manufacturer for help. The older generation machines are often misdiagnosed at this point, and the tech will suggest ordering or trying up to several parts, which can be very costly. Some of these parts may be needed and others will not. The challenge of only ordering one part at a time could result in delayed repair time with multiple shipments and on-site tech labor charges. When ordering several parts at a time, however, make sure to ask if the unused parts be returned for full credit or a refund with a re-stocking fee, or if they cannot be returned at all. Major replacement parts can cost anywhere from $3,000- $10,000 (not including service), even if the sensor is not involved. Warning: Buying parts other than sensors on eBay can be limited or difficult, and often dealer technicians will refuse to replace these parts due to liability issues.

“I’m sorry, this unit is discontinued, and parts are no longer available”

By law, X-ray manufacturers must make parts and support available for their equipment for around eight years after the machine was last sold. For example, if your machine was manufactured in 2007 and sales stopped in 2010, they are obligated until 2018 to provide replacement parts and support. That doesn’t mean if your machine is dated 2007, then you are already out of luck. If that model is currently still manufactured, then you have a long runway for parts availability. Many manufacturers are still providing parts and support beyond the eight required years, but the challenge for them is that these parts were not made by their own company, but by third-party suppliers. If those suppliers choose not to continue manufacturing the desired part past the eight-year requirement, then the X-ray manufacturer is left with only the parts that they have on their inventory shelves. This is a common issue with many X-ray manufacturers.

Replacing the unit

Replacing an X-ray unit is a costly proposition. Fortunately, digital panoramic unit pricing has come down significantly in recent years. In addition, many quality pre-owned X-ray options are also available. The challenge now becomes that your X-ray is down and you need a replacement in a short period of time. This time factor could limit your options and ability to negotiate the best price. Many X-ray manufacturers have ended exclusive distribution deals, so you can shop for the same X-ray model from several distributors for the best pricing. Depending on the repair status of your current unit, you may be able to receive some trade-in value based on the remaining parts. Perhaps this is the practice’s impetus to choose and upgrade from 2D to 3D. If you want to “buy” some time for additional research, you can also ask the new / used X-ray vendor to fix your unit with borrowed / loaned parts until the new X-ray is purchased.

So, when faced with the challenge of repairing or replacing your X-ray, ask yourself the following questions:

- What are the costs of the repair? Do they exceed the costs of purchasing a new or pre-owned unit?

- Can I get away with “patches” such as swapping a sensor between a pan/ceph unit or buying parts on eBay?

- If my X-ray is over eight years old, are parts still available?

- Can I allow enough time to research my options and compare pricing between vendors?

- Is now a good time to consider upgrading from 2D to 3D?

When possible, the best practice is start planning ahead for older X-ray equipment replacement. But, since you cannot always predict equipment failures, it never hurts to start researching your options today.

Your first patient after lunch is coming in for a second opinion consultation and bringing in diagnostic records from another orthodontic office. Consider the following scenarios:

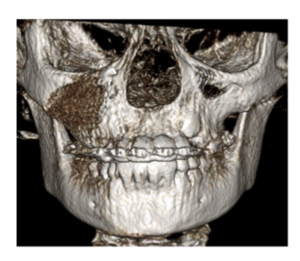

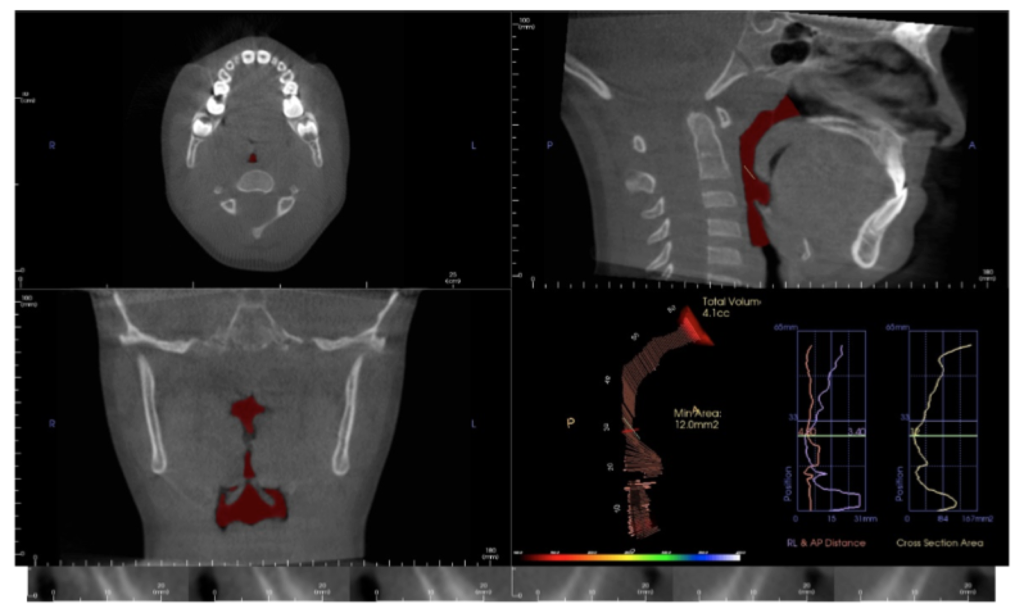

Your first patient after lunch is coming in for a second opinion consultation and bringing in diagnostic records from another orthodontic office. Consider the following scenarios: When diagnosing and treatment planning interdisciplinary patients, have you ever sent your three-dimensional images to a colleague? Have any of your patients requested a copy of their records for a second opinion? Or maybe, a patient declines a radiograph because another orthodontist has recently taken a CBCT image of the patient? In all of these instances, you will need to communicate with the other office to initiate the transfer of CBCT images. The purpose of this blog is to describe different methods used to share patients’ CBCT records via online means.

When diagnosing and treatment planning interdisciplinary patients, have you ever sent your three-dimensional images to a colleague? Have any of your patients requested a copy of their records for a second opinion? Or maybe, a patient declines a radiograph because another orthodontist has recently taken a CBCT image of the patient? In all of these instances, you will need to communicate with the other office to initiate the transfer of CBCT images. The purpose of this blog is to describe different methods used to share patients’ CBCT records via online means. In August 2014, I wrote an introductory article for this blog entitled “

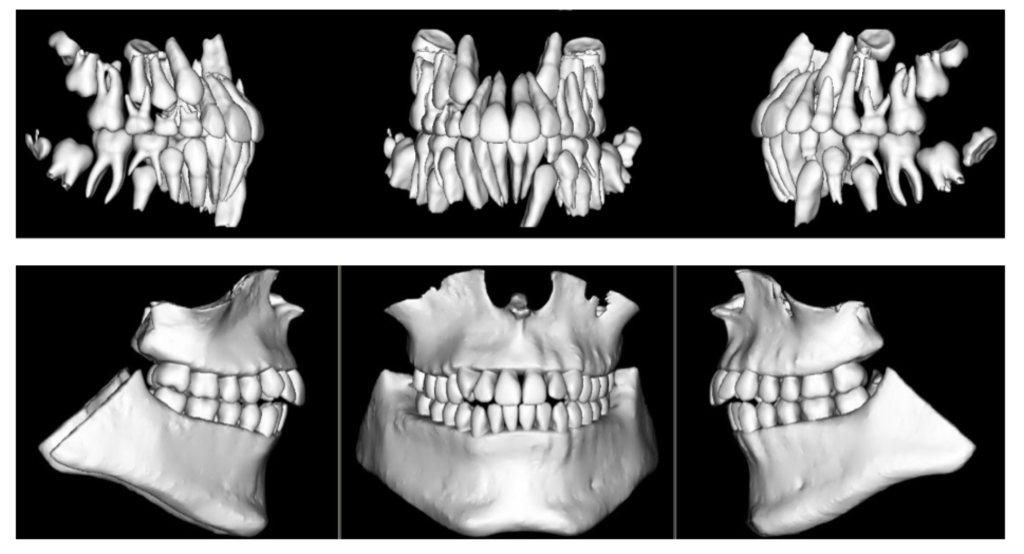

In August 2014, I wrote an introductory article for this blog entitled “ You will see pathology in the 3D data that isn’t visible with standard 2D imaging. When pathology is visible in 2D, the 3D data can more accurately ascertain location, extent, and character of the area of concern. This is beneficial to our patients.

You will see pathology in the 3D data that isn’t visible with standard 2D imaging. When pathology is visible in 2D, the 3D data can more accurately ascertain location, extent, and character of the area of concern. This is beneficial to our patients.

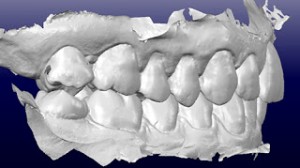

Indirect bonding was first introduced to orthodontics over 20 years ago and has become an integral part of many orthodontic practices and orthodontic labs worldwide. The four reasons/advantages for its inception are: 1) Indirect bonding has been widely viewed as giving the orthodontist the ability to achieve more accurate bracket placement on a static model and not having to deal with the clinical challenges with direct bonding on a patient, 2) The doctor can perform the final check for bracket placement at his/her own leisure and not under a set clinical schedule, 3) To improve clinical efficiency with decreased doctor chair time at the full bonding appointment, and 4) Finally, for improved patient comfort due to decreased time which the patient is in cheek retractors.

Indirect bonding was first introduced to orthodontics over 20 years ago and has become an integral part of many orthodontic practices and orthodontic labs worldwide. The four reasons/advantages for its inception are: 1) Indirect bonding has been widely viewed as giving the orthodontist the ability to achieve more accurate bracket placement on a static model and not having to deal with the clinical challenges with direct bonding on a patient, 2) The doctor can perform the final check for bracket placement at his/her own leisure and not under a set clinical schedule, 3) To improve clinical efficiency with decreased doctor chair time at the full bonding appointment, and 4) Finally, for improved patient comfort due to decreased time which the patient is in cheek retractors. It was not that long ago when we all relied upon our friendly postmen and postwomen for the delivery of our letters. Today the United States Postal service is scaling back mail operations in favor of package delivery, and the majority of our written communication is transmitted electronically. Is the delivery of healthcare, and particularly orthodontic care, headed for a similar fate? A Computerworld article, cited research by Deloitte, which projected 75 million of 600 million appointments in 2014 with general practitioners would involve electronic or eVisits¹. “Electronic visits or telemedicine are comprised of electronic document exchanges, telephone consultations, email or texting, and videoconferencing between physicians and patients. The vast majority of eVisits, according to Deloitte, are likely to focus on capturing patient information through electronic forms, questionnaires and photos.” In the state of Texas, new legislation has opened the door for physicians to be compensated for remotely providing care to children through a video connection to the school nurses’ office². Market forces including an expansion of access to care, increased efficiency, and financial incentives are driving all of these changes. Just as eMail though has not completely eliminated the need for our postal service, eVisits are not likely to eliminate the need for all direct patient to physician interaction. However, there can be no denying that technology is changing the manner in which healthcare is delivered and our specialty will not be immune.

It was not that long ago when we all relied upon our friendly postmen and postwomen for the delivery of our letters. Today the United States Postal service is scaling back mail operations in favor of package delivery, and the majority of our written communication is transmitted electronically. Is the delivery of healthcare, and particularly orthodontic care, headed for a similar fate? A Computerworld article, cited research by Deloitte, which projected 75 million of 600 million appointments in 2014 with general practitioners would involve electronic or eVisits¹. “Electronic visits or telemedicine are comprised of electronic document exchanges, telephone consultations, email or texting, and videoconferencing between physicians and patients. The vast majority of eVisits, according to Deloitte, are likely to focus on capturing patient information through electronic forms, questionnaires and photos.” In the state of Texas, new legislation has opened the door for physicians to be compensated for remotely providing care to children through a video connection to the school nurses’ office². Market forces including an expansion of access to care, increased efficiency, and financial incentives are driving all of these changes. Just as eMail though has not completely eliminated the need for our postal service, eVisits are not likely to eliminate the need for all direct patient to physician interaction. However, there can be no denying that technology is changing the manner in which healthcare is delivered and our specialty will not be immune.